When at the British Museum just before Christmas I bought a fascinating book, a Jungian tome on symbols and archetypal images. The text is interesting, though not perhaps as expansive – or as well-referenced – as it could be. More inspiring is the eclectic choice of illustrations sourced from around the world and spanning a period of over 2000 years. It is rare to see such a diverse collection of images, with most art history books focusing on the West, or on a specific subject matter such as 18th century Japanese art, or Burmese bronzes. The illustrations in this book are an affirmation of the genius and creativity of man and also of the power of the collective unconscious.

Many of the pictures are not available online but I have made a small selection below. All the quotes are from the book: (Eds.) Ronnberg, Ami & Martin, Kathleen, 2010, The Book of Symbols, Reflections on Archetypal Images: Koln, Taschen

Hokusai (1760-1849), Amida Waterfall on the Kiso Highway, Japan.

I find this print captivatingly grandiose and delicate at the same time. The depiction of a waterfall is highly stylised, majestic, and ethereal, its scale emphasised by the inclusion of three small men picnicking on a precipice.

‘The descent of a great mass of water can … overwhelm us. The waterfall has been imagined as a stream feeding the dark realms of the underworld and circling up to issue again from craggy heights. It has been suggested the descent of the immutable into an ever-dividing stream that defies capture, cannot be contained, is eternal movement, eternal change, generating life and death … The waterfall itself is an emblem of balance. Chinese landscape paintings portray the waterfall in contrast to the upward movement of the rock face over which it descends, and the dynamic movement of its rushing waters with the stillness of the rock.’ (p48)

Uccello, St. George and the Dragon, 1465, Italy.

This bold composition with its vivid colouring is one of my favourite paintings at the National Gallery, London. St.George, clad in armour and riding a white horse, is in the midst of saving the princess by spearing the dragon. Behind him is a dark forest and spiralling clouds, contributing to the drama of the scene. The princess, however, stands, unperturbed, holding the dragon on a leash as though it were a pet dog.

‘Long ago, the dragon began as a winged or flying serpent, expressing the primal harmony between the subterranean and aeriel dimensions … As an image of the unconscious, the dragon moves in and out of psyche’s darkness, showing only parts of itself, evanescent.’ (704)

“Inside the Bubble of Love,” a detail from The Garden of Earthly Delights by Bosch, c. 1504, the Netherlands.

Hieronymous Bosch – the first surrealist? An altogether bizarre scene which is on the one hand, distinctly medieval, and on the other hand oddly 21st century with its peculiar juxtaposition of objects and nature, and almost nightmarish in its conception, with giant birds, oversized foliage and small people. It brings to mind Roald Dahl’s ‘James and the Giant Peach’ which terrified me as a child.

‘The archetypal symbol of a bubble exists in the psyche beyond time and space. It constitutes an invisible reality imaged by mystics throughout the ages, a round nothingness that is paradoxically the primordial source of all.’ (52) ‘Throughout history, the translucent bubble has inspired contemplation of the infinite and the eternal .. The translucency of the bubble, introduces … the numinosity, etheriality and spirituality associated with the celestial light of heaven.’ (52)

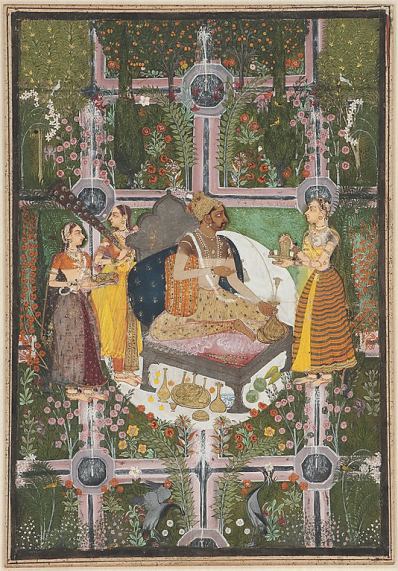

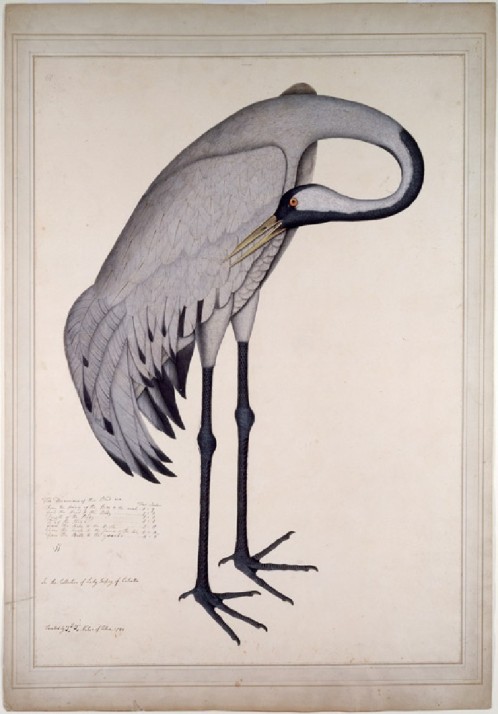

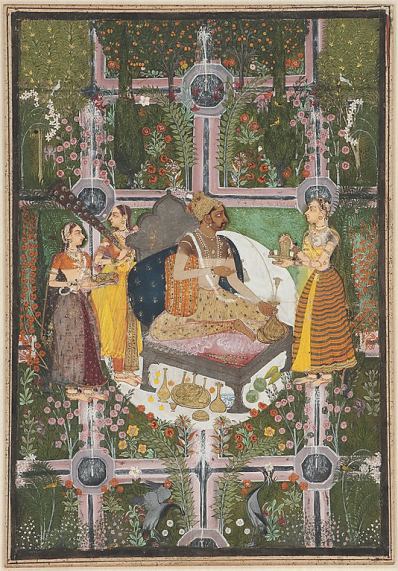

Kotah Master, Rana Jagat Singh II of Kotah, Rajasthan, c. 1750 – 1800, India.

I was drawn to this painting because I visited the palace at Kota earlier this year (see a previous post). Today the palace is a little decrepit, with a few splendid reminders of how rich and extravagant this complex once was. This miniature depicts the gardens of the Rajput palace when they were still very much alive and in use. Looking at this painting is strangely nostalgic, albeit nostalgic for something never experienced.

‘Eighteenth-century patron Rana Jagat Singh II of Kotah, India, cultivated the arts as one might cultivate a fine garden … The Kotah master … has honoured his patron by depicting him enthroned in the center of a flourishing garden, divided into four sections of pink and orange blossoms, lush vegetation and fountains flowing with water.’ (146)

‘In almost all cultures and religions, the garden represents a sacred space, a uniting of the conscious self with its unconscious source. Muslims speak of gardens as states of bliss and call Allah “the gardener.”‘(146)

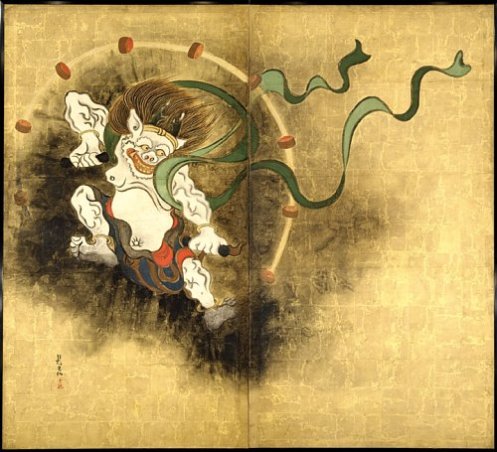

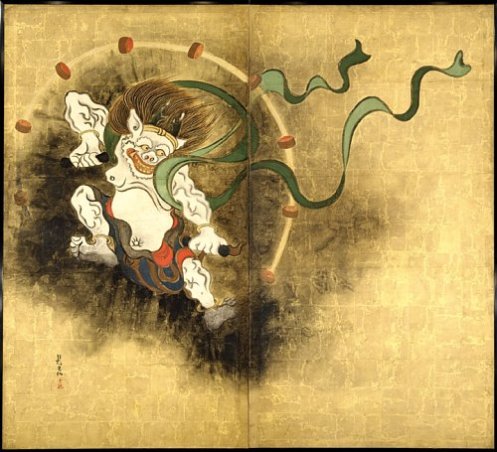

Ogata Korin (1658-1716), Raijin, detail from Gods of Wind and Thunder. Japan.

Raijin is the Japanese god of thunder, here looking rather comical.

‘Stormy of countenance, the Japanese god Raijin makes thunder as he pounds on a great ring of drums. The crash of thunder can still unnerve us. While science has explained thunder as the explosive expansion of heated air in lightning’s path, it was in former times the signature of the highest, earthshaking gods: Thor, Zeus, Yaweh, Indra, Baal, Taranis. Always ambivalent, the gods of thunder and lightning could bring either death and destruction or fertility and new life to humankind and its surroundings.’ (68)

William Blake (1805), The Descent of Man into the Vale of Death: “But Hope Rekindled, Only to Illume the Shades of Death, and Light Her to the Tomb,” England.

A magnetic example of Blake’s visionary world. Here ‘death is depicted as an “under” world, to which the spirits of the dead initially descend before Hope illuminates the possibility of an eternal home.’ (432) The underworld is a labyrinth of catacombs into which a steady stream of figures are descending from the hills above.

‘Myth and ritual from the oldest times attest to the transformative possibilities of descent. It is return to a transpersonal matrix for rebirth, the obtaining of treasured self-knowledge from realms of luminous darkness, or a boon of understanding that brings “up” to collective consciousness the genuinely profound.’ (432)

Posted in Uncategorized

Tags: http://www.taschen.com/pages/en/catalogue/art/all/06703/reviews.the_book_of_symbols_reflections_on_archetypal_images.1.htm

Tilly Kettle, Warren Hastings.

Tilly Kettle, Warren Hastings.

This same type of beautiful elephant is found on most monuments of the fifth century CE.

This same type of beautiful elephant is found on most monuments of the fifth century CE.

This small fragment depicts a kirtimukha or lion head spewing pearls. It is an image found on most early temples.

This small fragment depicts a kirtimukha or lion head spewing pearls. It is an image found on most early temples.

Recent Comments